Camembert

"This cheese doesn't smell like much...I want to wrap this cheese MYSELF. STOP HELPING ME. How much longer until we can eat this?"

When Wyatt was a baby, there was a flurry of discussion around how French parents raise their children. Most of it stemmed from Pamela Druckerman's book, Bringing Up Bébé, which I found thoroughly enjoyable. The book reviews, articles, and interviews surrounding Bringing Up Bébé often focused on how well French children eat, even in daycare. Without exception, it seemed tiny children ate multi-course lunches created from a wide variety of fresh ingredients. The children sat for the whole meal, used a knife and fork and drank politely from a glass that was made of actual, breakable glass. The whole scene sounded so perfect that it made me want to trade-in our cultural food identity. I did not want to raise a notoriously picky eater who behaved atrociously at the table. I wanted to raise a child who was, broadly speaking, French about food. I realized I stood very little chance of ever pulling this off, considering I'm an American who has eaten innumerable sad desk lunches and has experienced French food life only while on vacation. And yet, likely because I'm an American, I figured there was no harm in taking a whack at it. We were already on the fringe of standard American food life, after all. For example, before Wyatt started eating solid food, our pediatrician suggested that a great first food would be beef stew. I remember blinking a couple of times and asking, "Really?" before accepting the challenge. After that appointment, I found a great butcher, made my first beef stew, and then I puréed most of it for baby Wyatt.

Beef stew aside, I felt I needed to improve my cooking range and abilities. I started looking at what French kids eat, and I realized I didn't know what half of it was, never mind how to cook it. I read Karen Le Billion's posts of school lunches in France, and as I translated them and looked up recipes, I began to feel daunted: Variety! Balance! Sauces! Cheeses! It seemed like a lot, and at the time, I had a somewhat limited cooking repertoire. But it all began to make sense for me when Wyatt was 18 months old and Marc bought me Wini Moranville's La Bonne Femme Cookbook for my birthday. La Bonne Femme remains one of my favorite cookbooks. The recipes are straightforward, easy to prepare, and great to eat. The flavors Wini Moranville highlights make for truly delicious meals with just enough flair to make me feel a little bit fancy without extra work. Thanks to this book, I finally learned to cook meats with pan sauces, and I began to appreciate really simple salads. In a short time, I was applying what I had learned from the recipes to make widely varied lunches for Wyatt and me. I'd prep the ingredients in the morning while he was eating breakfast, and then I'd cook our lunch in under 30 minutes starting around 11:30. Chicken Calvados was one of our favorites, and all of her simple salads, including grated carrot salad and celeri remoulade, were in heavy rotation.

I took our lunchtime cheese course pretty seriously, too. I did my best to choose small pieces of different kinds of cheese at the cheese counter so that we'd have a wide variety over any given week or two. One of Wyatt's favorites from the beginning was brie, Fromager d'Affinois, to be exact. It's still one of his favorites, and brie is the cheese he has been most excited to make since we started working from The Art of Natural Cheesemaking.

Much to Wyatt's disappointment, we couldn't start a brie (or Camembert-style) cheese for awhile because it has been simply too warm for us to age it in the garage. We did, however, start a recipe about a month ago.

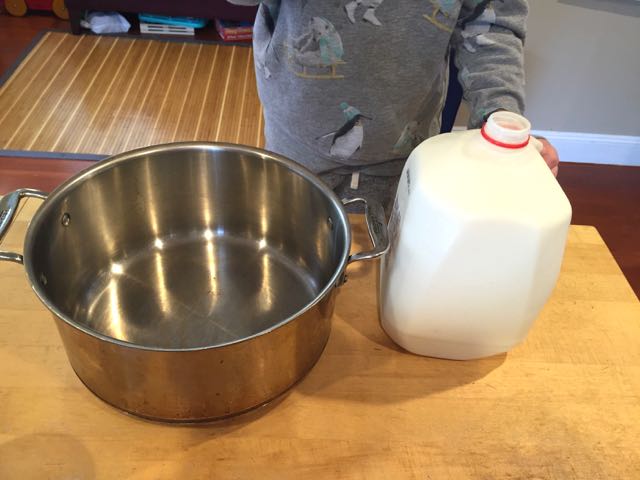

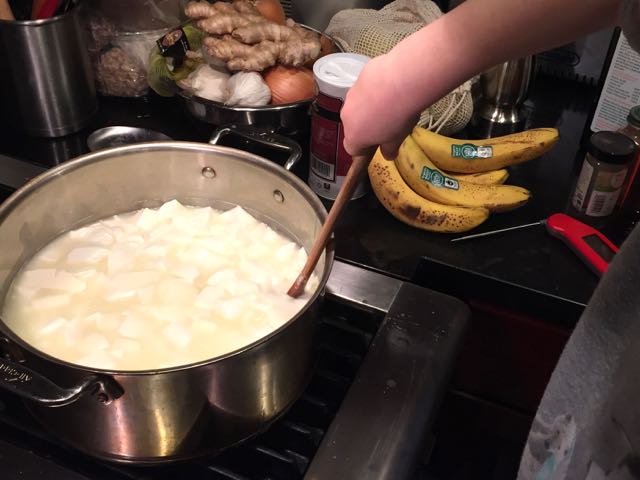

We opted for two smaller cheeses, Camembert-style, over a larger brie. Our Camembert started out very much like the feta and mozzarella we made. We began with a gallon of raw cow's milk. We heated it to baby-bottle warm, and then we added kefir culture and rennet. We kept the milk warm while the curd set. Once we had achieved a clean break in the curd, I sliced the curd into cubes and we stirred the pot occasionally while allowing the curds to firm up a bit more. When the curds were the consistency of a well-poached egg, we poured the whey off and reserved some for a washing brine. We then carefully strained the curds by hand into our cheese forms on our makeshift draining table. The cheeses drained for about a day, and once they were firm, we salted them. We let the formed cheeses dry for another day or so, and then we put them in the cheese cave.*

During the first week of aging, we wiped down the rinds of the cheeses every other day with a cheese cloth dipped in the washing brine we had prepared from the reserved whey.

Initially, we had no place in the garage that was cool enough (50 degrees) to keep the cheese cave. I emailed David Asher, curious if close to 60 degrees would be acceptable. He suggested that we try the refrigerator instead. So the cheese lived in its cave in the refrigerator for the first week. After that, the weather cooled a bit more, and I located a spot in our garage that was consistently about 50 degrees, so I moved the cave there.

The next challenge became how to maintain 90% humidity inside the cave. It was easy for the first week in the refrigerator when the humidity was low. I just added a bit of clean sponge that I had dampened with water in order to raise the humidity in the cave. But once the cave was in the garage, the temperature was warmer and the humidity stayed stubbornly at 99%. Even worse, one of the cheese rounds wasn't getting the puffy white mold on it. It was staying yellow and a little sticky, which wasn't good. I swapped out the cheese aging mat for a dry one, and I added some silica gel packets to the perimeter of the cave. Those adjustments resulted in no appreciable change. Wyatt and I then tried making our own packets of calcium chloride, otherwise known as pickle crisp, to place at opposite ends of the cave. The first packets we made worked almost too well, and the humidity dipped to 80%. We remade the packets with fewer granules, and that seemed to work better. Regardless, I continued to monitor the humidity levels in the cave daily because the whole process of adjustments had been so incredibly imprecise.

This weekend, it was time to wrap our cheese in cheese wrapping paper so it can continue its aging process for another month in the refrigerator. The rounds are now tucked safely in the back of the cheese drawer. And tomorrow, Wyatt and I are planning to make Chicken Calvados for dinner, for old time's sake.

*Our cheese cave is almost embarrassingly basic. I bought a shoe box sized plastic box with a lid at our little, local hardware store, and that's the cave. I place a bamboo aging mat on the bottom of the box, and I use an inexpensive hygrometer that I picked up in the garden center of a large hardware store. Because we had a mouse problem in our garage several months ago, I put the shoe box sized box into a slightly larger box with a locking lid.