Whey Ricotta

"Dad. Guess what? Mom ALMOST let the whey boil over! You should have seen the foam on the top of the pot!"

Before making feta, I did not have a good appreciation of how much of reductive process cheesemaking really is.

When I ordered our cheesemaking supplies from The Cheese Connection, the incredibly helpful Kallijah informed me that a gallon of milk makes about a pound of cheese. But what this actually meant in real life was that our gallon of goat's milk made just over a pound of feta, and left about 15 cups of whey. If you're not up on your conversion factors, let me help you out. There are 16 cups in a gallon, so the leftover liquid was only a cup less than our original gallon of milk. I suddenly began to understand why good cheese is so expensive.

And I was left with the question of what to do with all that whey. Fortunately, David Asher anticipated this question and included a chapter on "Whey Cheeses" in The Art of Natural Cheesemaking. In the chapter, David provided a variety of sensible suggestions on how to use whey, and there is a picture of him feeding whey to pigs, and a picture of him watering his garden with whey. Wyatt, a child of the California drought, looks for any opportunity to pour liquid anywhere, so he was in favor of finding a pig to feed, or barring that, pouring the whey on our garden. I, on the other hand, a grown-up involved in a Cheese Project, was in favor of trying to make one of the cheeses with it instead. Eventually Wyatt agreed to make whey ricotta.

As David explained in Chapter 22, Whey Cheeses, "Italian, for 'cooked again,' ricotta refers to the second making of cheese from one batch of milk: the milk is first 'cooked' to make Parmigiano Reggiano or pecorino or some other Italian cheese, and the leftover whey is then 'cooked again' to make ricotta."

We had just over a half-gallon of whey available to play with, because the rest of it had been used for the brine to age the feta, or I had spilled it on the floor. A half-gallon was about half of the amount of whey required for the "Slow Ricotta" recipe, but I figured we could try the recipe anyway and see what happened. If we only got an ounce or two of ricotta, so be it. It's not like we had a pig starving for whey in our back garden.

Here's what we did:

First, we left the whey to ferment at room temperature for 24 hours. Monday afternoon, we poured the whey into a pot and brought it to a boil. David specifically warned in his recipe to remove the pot from the burner right as the whey comes to a boil so it doesn't boil over. Unfortunately, I forgot for a few minutes that the pot was even on the stove because Wyatt had begun conducting an imaginary orchestra (with they aid of a tinker-toy stick) in Rimsky-Korsakov's "Flight of the Bumblebee" from his San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Concerts for Kids CD. I lost track of the whey, and just as the foam was about to cascade over the rim of the pot, I happened to glance over at the stove, gave a little yelp, and pulled the pot off the burner just in time.

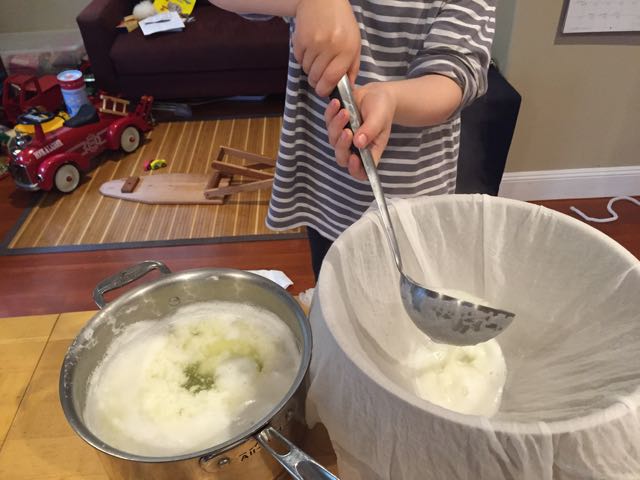

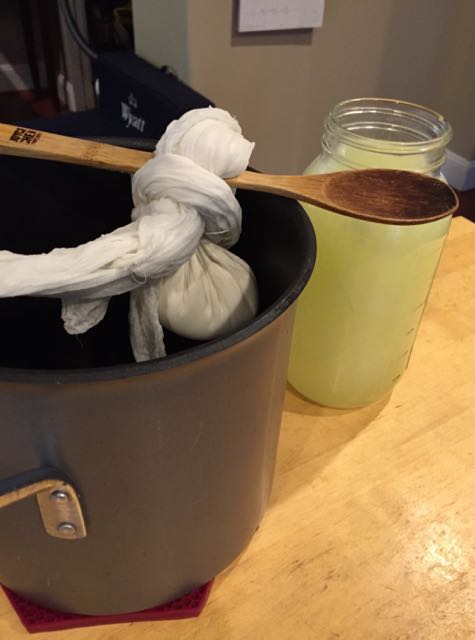

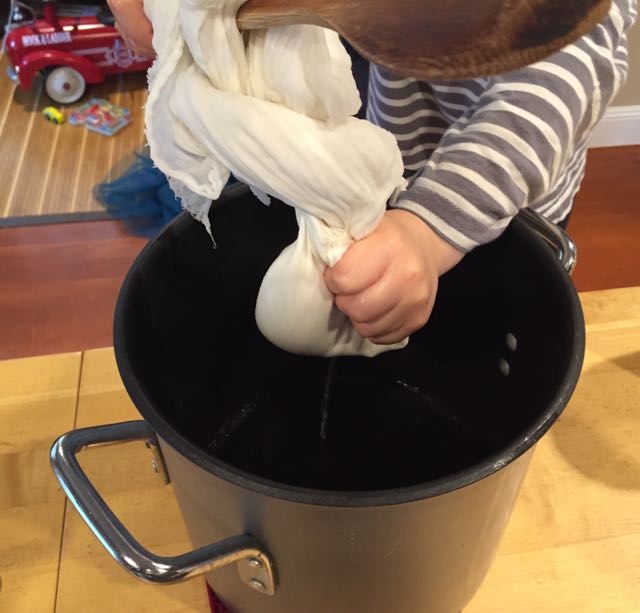

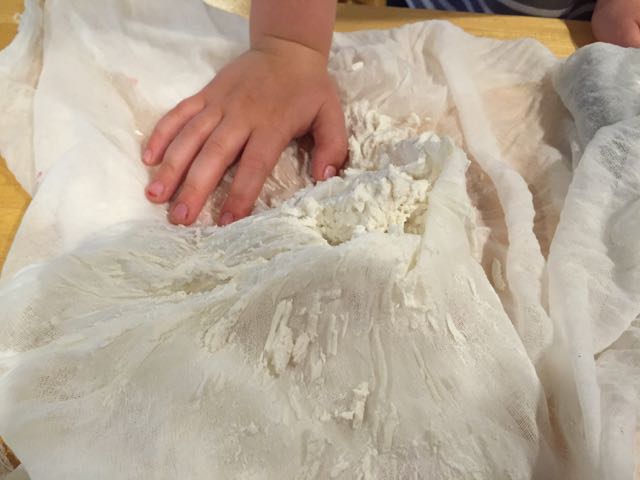

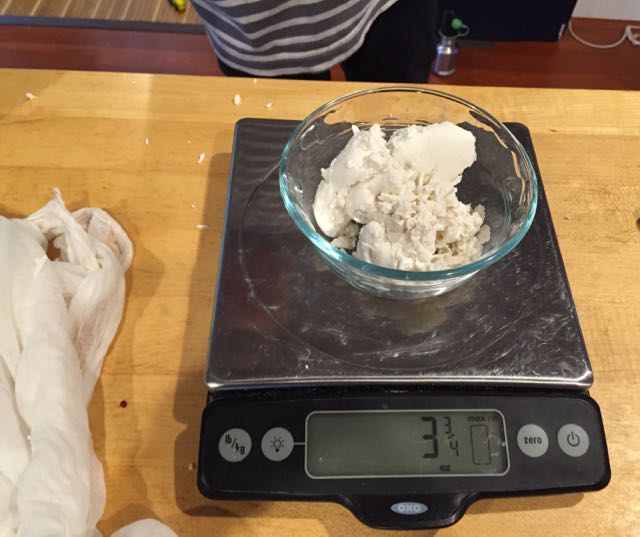

Back on task, we let the whey settle, and sure enough, there were little clouds of ricotta curd that had pulled out of the whey. We strained the ricotta in some cheese cloth and hung it to let it drain and cool.

Once the cheese had drained (and yes, we probably shouldn't have, but we squeezed the hanging cheese just a little bit to move the process along) and cooled, we weighed it, salted it and ate it for dessert with some fruit. I was impressed that we got almost four ounces of ricotta. The cheese was soft, creamy, and thanks to the fermentation step, had a depth of flavor I have never before tasted in ricotta.