Feta-tastic!

"Mom. Can I just please try this? With the salt? PLEASE?"

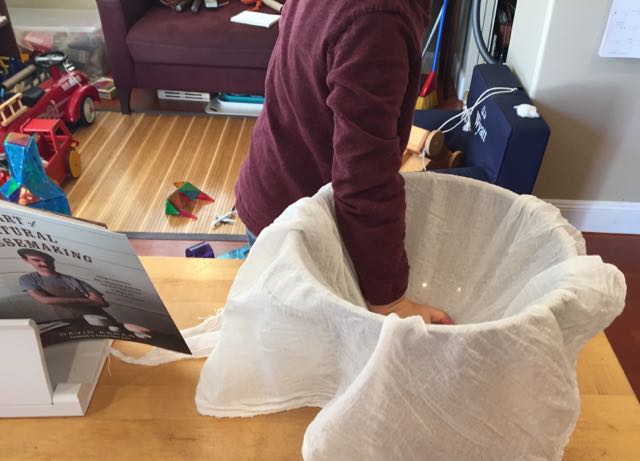

Originally, I had planned to work through the recipes in David Asher's The Art of Natural Cheesemaking in the order that they appear. But as the rest of North America heads into autumn and cooler temperatures, San Francisco is entering summer. I checked the temperature of our normally chilly garage last week, when temperatures were in the 80s and above, and the garage was over 70 degrees. That's way too warm for aging chèvre, which is the next chapter in the book.

But we were on a roll, and the idea that our project could be stymied by warm weather seemed wrong, or at least unacceptable, to me. I skipped ahead to the chapter fifteen, on feta: "Feta is a cheese that is aged by submerging it in a brine made of its whey. Started as basic rennet curds, feta is defined by this brine-aging. Brine-aged cheeses are most popular in warmer climes, where salty brines preserve cheeses well despite high temperatures and without refrigeration." Perfect!

On Saturday, I bought a gallon of raw goat's milk that had just been delivered to Rainbow. Ideally, we would have started the cheese on Saturday, but Saturday was just too busy. Also, I had forgotten to make the active kefir we would need for our cheesemaking. So on Saturday, I started the kefir that would be ready the next day.

We started the feta on Sunday and finished on Monday. Here's what we did:

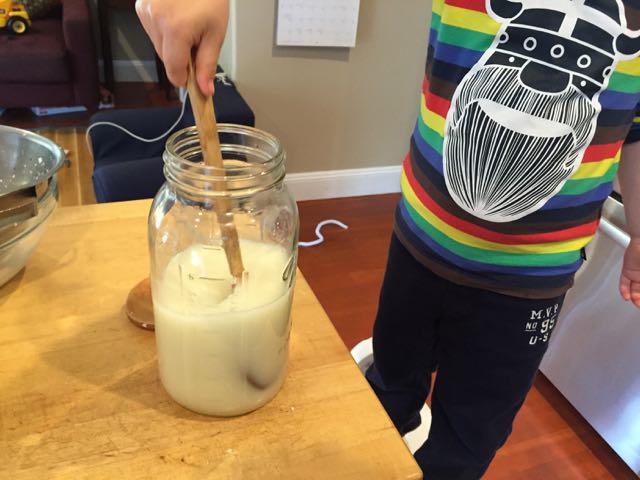

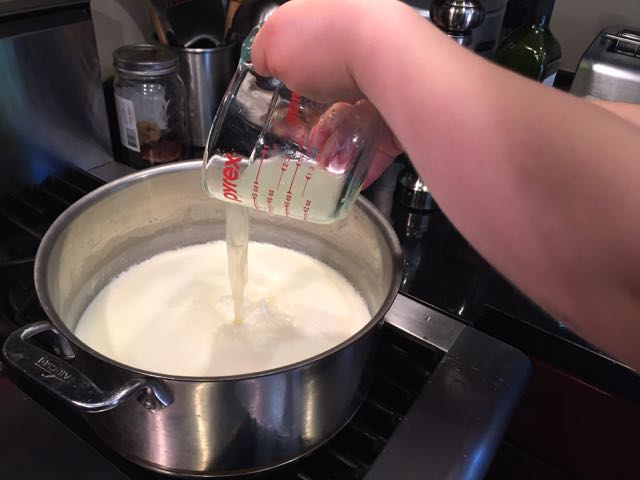

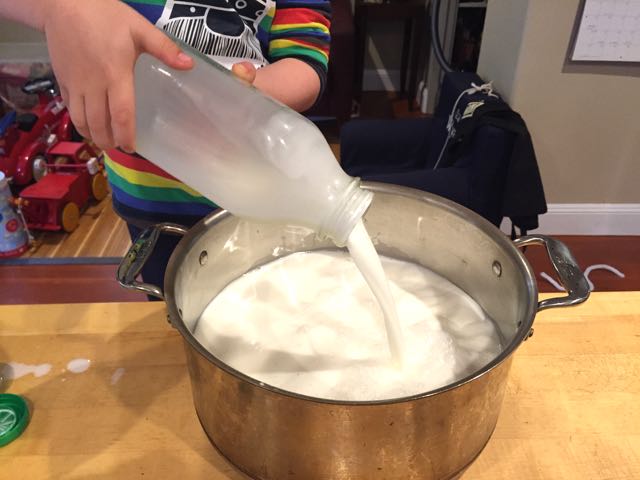

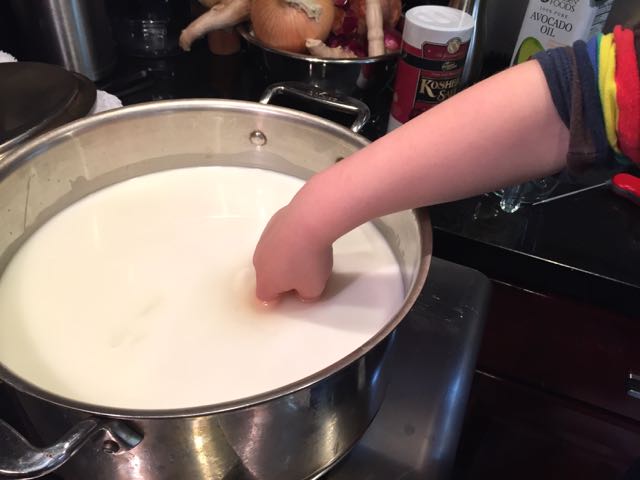

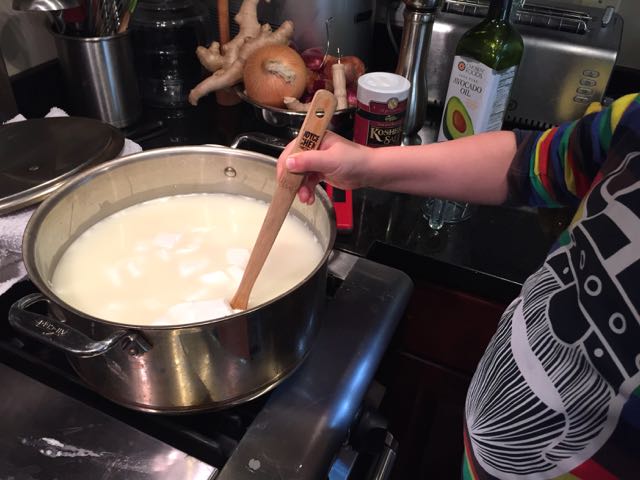

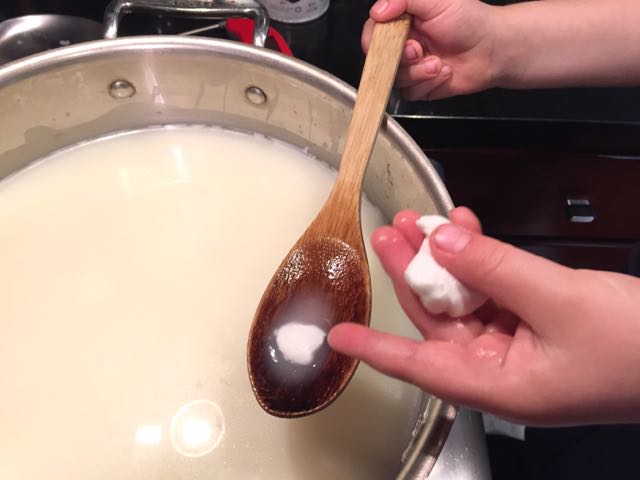

On Sunday morning, the kefir was ready, and we were eager to get started. But first, we learned what raw goat's milk tastes like. It's has a pretty distinctive taste, Wyatt said it was like hay. I don't know when he has ever eaten hay, but that's a different issue. He also said he liked the bit that he tried, thought that it tasted nothing like cow's milk, and he added that he probably wouldn't want to actually drink a glass of it. After pouring the milk into the pot, we warmed it, and added the strained, active kefir. We covered the pot to keep the milk at 90 degrees for an hour.

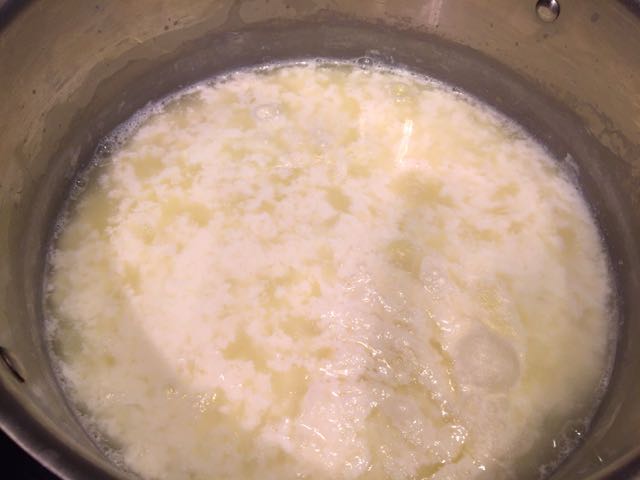

Keeping the pot warm was where I made my first mistake. After reading about how hard it can be to keep the milk warm enough, and how your cheese may fail if the temperature drops too low, I wanted to be sure that the milk stayed warm enough. And as you may have already guessed, I overcompensated. I brought out bath towels to swaddle the pot, and I turned the oven on, to keep the top of the stove warm. By the end of the hour, I measured the temperature of the milk, and it had risen to 99 degrees. This was obviously not ideal, but I rationalized (without any science or research, mind you) that it would probably be fine. I told myself that the pot hadn't been that hot for the whole hour, and I also figured that people in hot places drink kefir, so we should just push on. But before we continued with the recipe, we let the milk cook to 90 degrees, and I turned the oven off.

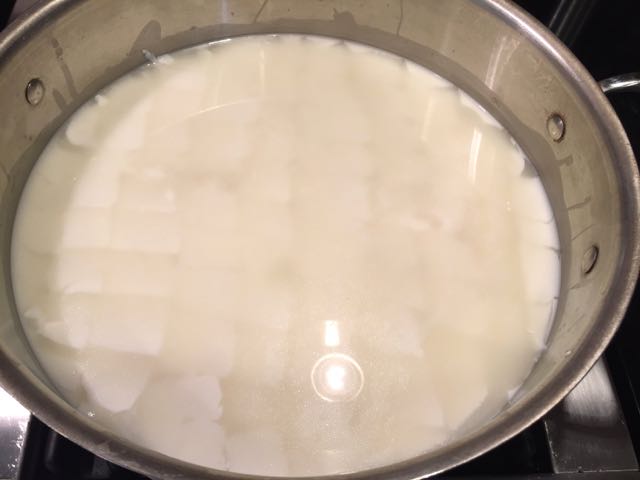

Once the milk had cooled a bit, we added the rennet that we had dissolved in water, and then we covered and swaddled the milk pot again for an hour. The stove had cooled off by that point, but I checked the temperature of the milk after 30 minutes, and it was 3 degrees warmer than it was when we started. So I removed some of the towels and uncovered the pot so it could get back to 90 degrees for the rest of the hour.

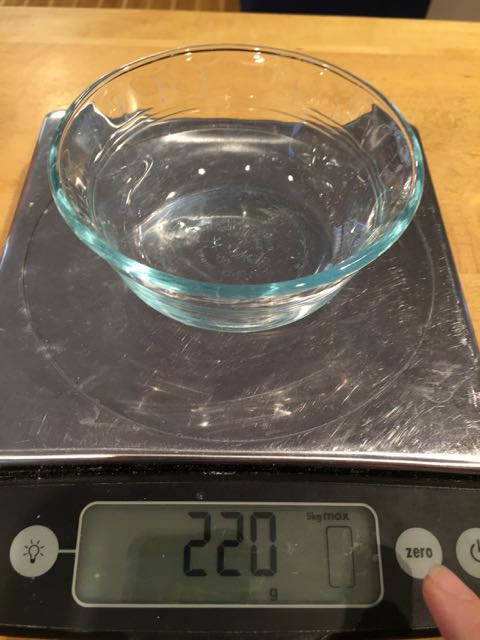

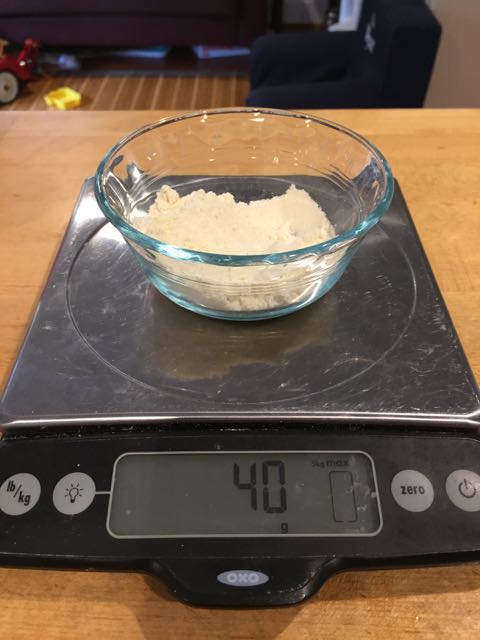

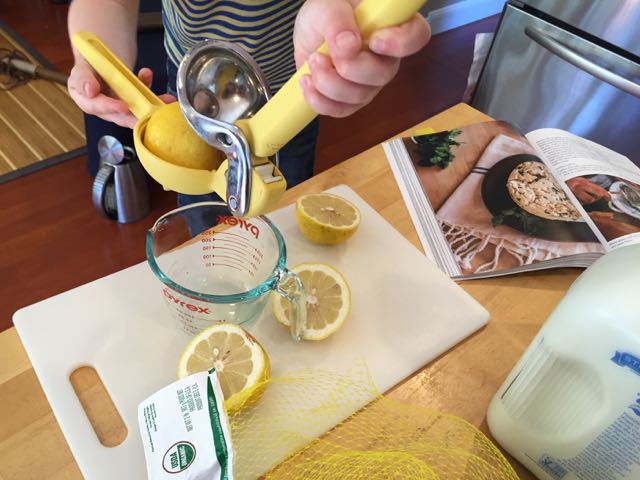

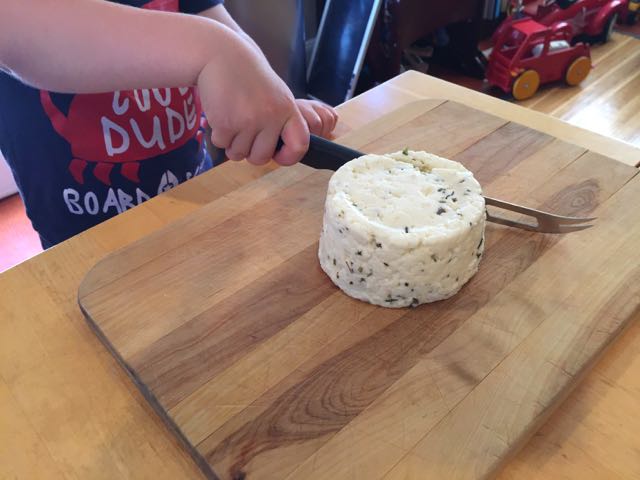

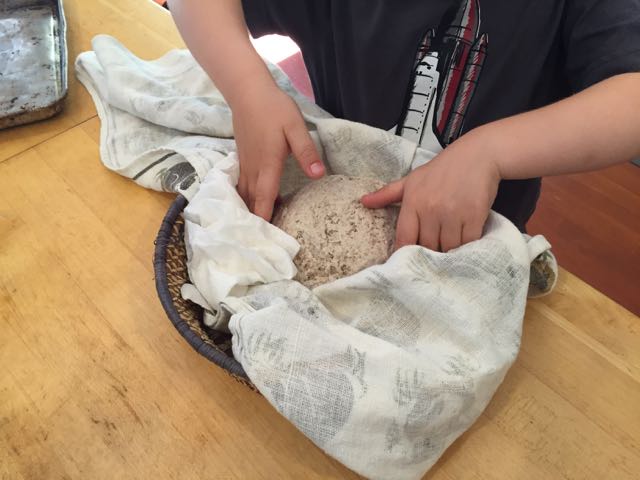

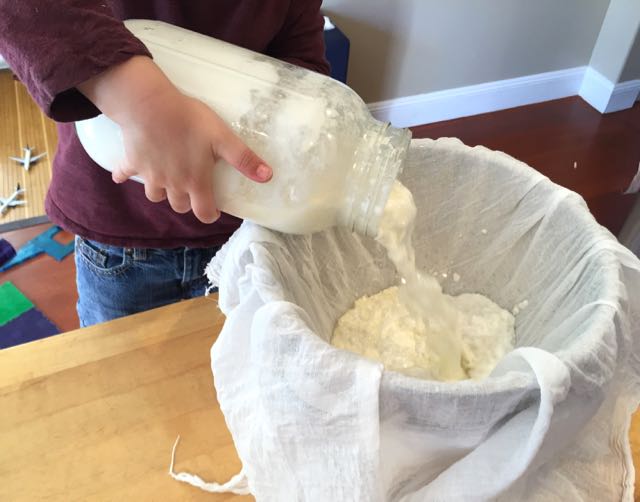

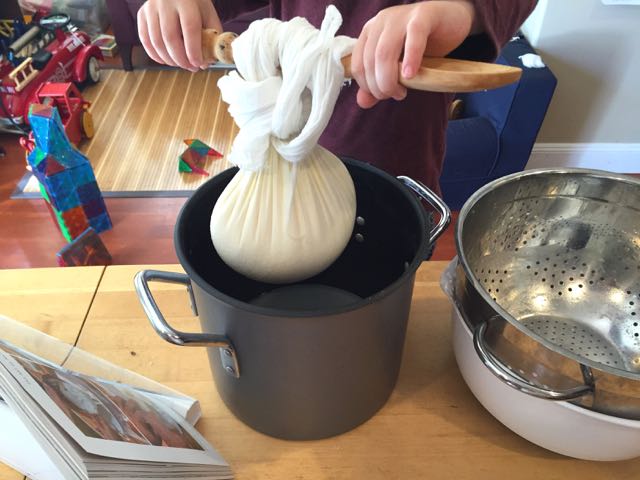

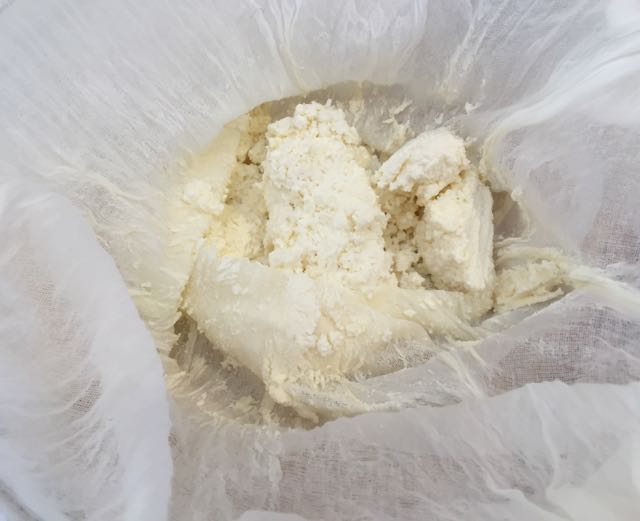

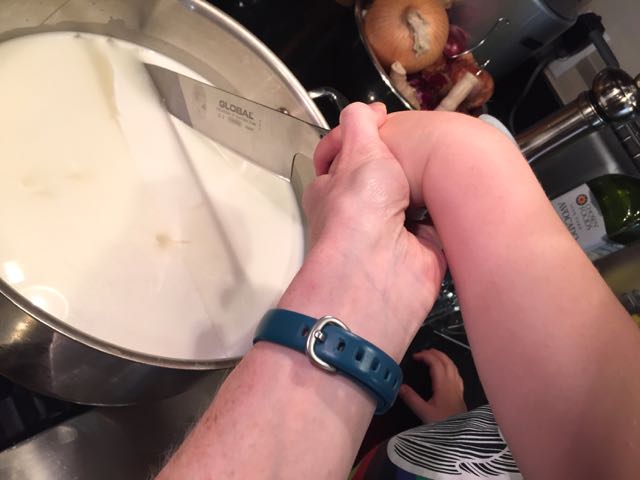

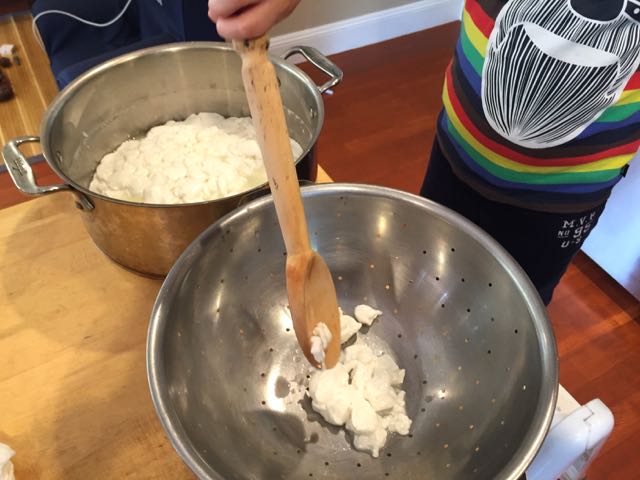

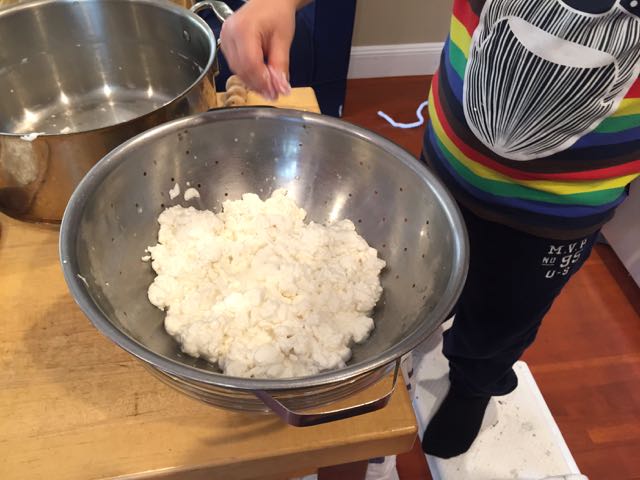

Next, we checked for a clean break of the curd, and we had one. At this point I was absolutely overjoyed that we actually had curd--its was the first obvious clue that we were on the right track with the recipe. Then we had to cut the curd, which is tricky in a round pot with a regular knife and a 4-year old who wants to do everything himself. But we managed, and the curds that we missed, we just cut them up later as we found them when we were stirring. We poured off the whey, salted the curds, and we set up our cheese press from last week, this time with cheese cloth in it, so we could flip the whole cheese occasionally. It worked perfectly.

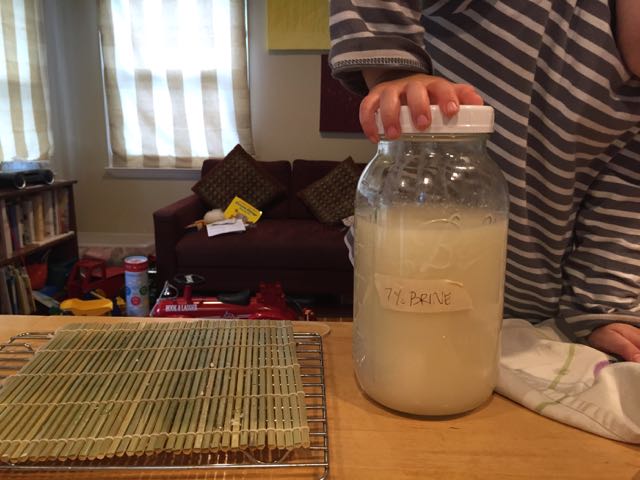

We then prepared our salt brine, and I managed to pour a good amount of whey all over the floor. I also splashed some on Wyatt's socks (he loves to add that part of the story). In my defense, our four-cup glass measuring cup pours terribly for some reason, and I had forgotten how badly it pours until I was standing in a puddle of whey.

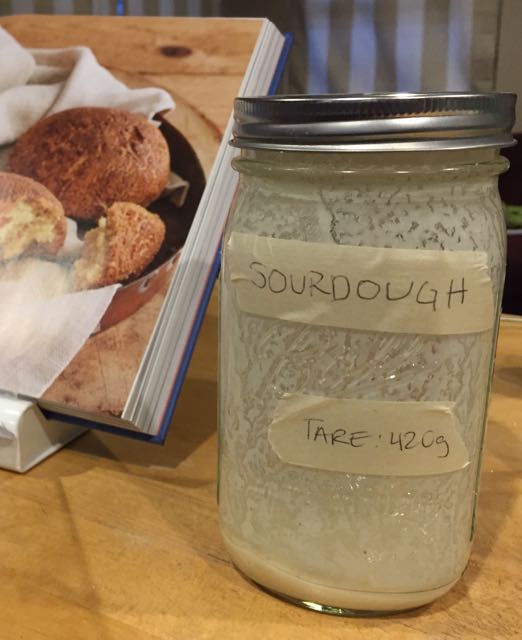

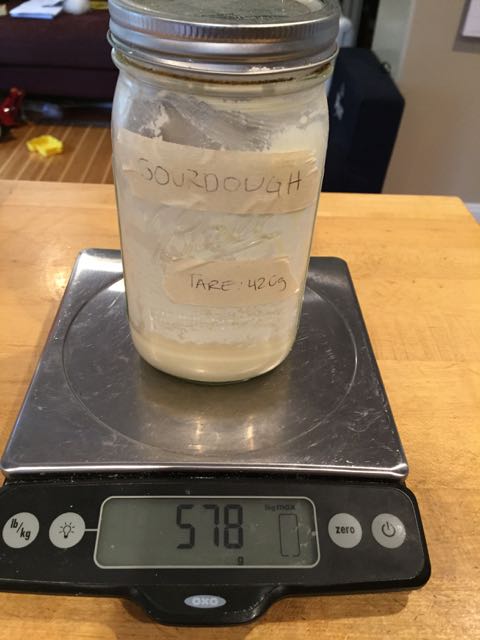

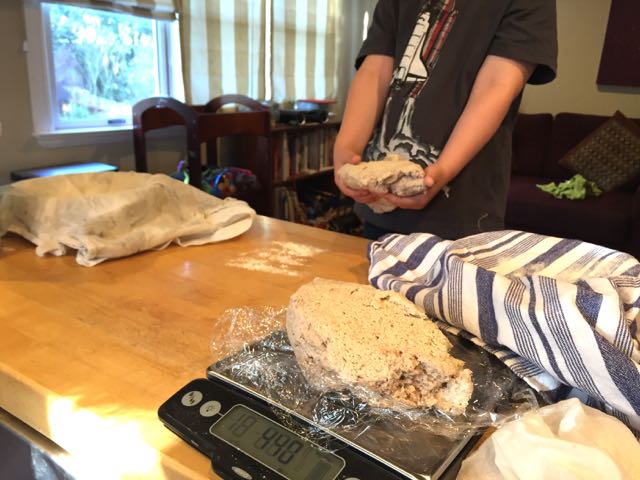

After the cheese had been pressed and was cool, we cut the block of cheese (which weighed just over a pound) into four pieces so it would fit in our jar with the brine. We salted the surfaces, and we set the quarters of cheese to dry on the aging mat for 24 hours. We flipped them occasionally so they would keep their shape.

On Monday afternoon, we checked our cheese, and they had lost another tablespoon or so of liquid. We had no idea whether they should dry for longer or not, but we figured they were probably fine to go into the jar of brine. And good news! They sank right to the bottom of the jar, and stayed there.

We put the jar in the refrigerator, and we now have to wait two weeks before we can try them. As Wyatt said, "Two weeks? That's not so long, right? That's like tomorrow, and then after tomorrow, and then it's two weeks!" He has such a good attitude for making cheese.